Amazon Deal for Whole Foods Starts a Supermarket War

by RACHEL ABRAMS" and by JULIE CRESWELL" JUNE 16, 2017

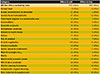

Walmart, Target, Kroger and Costco, the largest grocery retailers, all tumbled on Friday. And no wonder.

Grocery stores have spent the last several years fighting against online and overseas entrants. But now, with its $13.4 billion purchase ofWhole Foods,Amazonhas effectively started a supermarket war.

Armed with giant warehouses, shopper data, the latest technology and nearly endless funds — and now with Whole Foods’ hundreds of physical stores — Amazon is poised to reshape an $800 billion grocery market that is already undergoing many changes.

And much of the battle is expected to take place online, Amazon’s home turf.

“This shows that online is going to be very dominant in the grocery business — and very quickly,” said Errol Schweizer, a former Whole Foods executive.

The grocery business is facing a slew of upstart companies trying to figure out how to make a business of getting food on the kitchen table. Instacart delivers food from grocery stores to doorsteps, while FreshDirect delivers from its own warehouse. Blue Apron delivers boxes of food packaged to make meals.

In addition, Lidl and Aldi, two European discount grocers, have recently announced enormous expansions in the United States. Aldi plans to invest $3.4 billion to grow from 1,600 stores to 2,500 stores by 2022, while Lidl, which recently opened a handful of locations, plans to operate 100 by the middle of next year.

They are taking on a handful of major companies that have dominated the grocery market. Walmart supercenters, Kroger, Safeway and Publix accounted for about 36 percent of the market in 2013, according to the most recent data from the United States Department of Agriculture.

While the grocery giants have been under attack, they have advantages of their own. Walmart has 4,500 stores, for example, compared with the 460 Whole Foods, putting it in far more markets. Walmart has also tried to move swiftly into e-commerce, setting up grocery pickup at many stores.

A spokesman for Walmart, Randy Hargrove, said the company felt “great” about its “fast-growing” e-commerce and online grocery businesses.

But even before the deal, many of the stores have been showing signs of stress. On Thursday, shares in Kroger fell nearly 19 percent after the company lowered its guidance.

On Friday, the company put on a strong face.

“As we’ve done in the past, we will evolve our business to deliver what our customers want and need today and into the future,” Kristal Howard, a spokeswoman for Kroger, said in an email.

Whole Foods has had its own struggles. Once a pioneer of the organic foods movement, Whole Foods has more recently struggled to shed its image as too pricey, too upscale and too out-of-touch with customers who want more natural foods at more affordable prices. It recently overhauled its board, and Gabrielle Sulzberger, a?private equity?executive who is married to Arthur O. Sulzberger Jr., the chairman and publisher of The New York Times, was named the company’s chairwoman.

In recent years, competitors moved into its niche. Kroger and Albertsons have bulked up their organic offerings, and organic food has been one of the strongest areas of growth in the grocery business: Last month, the Organic Trade Association announced that sales of organics had increased by 8.4 percent to $43.3 billion, or more than 5 percent of grocery sales.

But with Amazon, the equation changes entirely.

It is unclear how Amazon will use Whole Foods, as the company would not go into detail about its plans. Jeff Bezos, Amazon’s chief executive, is known for making unconventional decisions. But he is also known for having big ambitions, and that could mean a more frontal assault on Walmart — a face-off between the old and the new dominant forces in the retail world.

Any heated competition among retailers could be a win for consumers who will be able to pick up their organic sugar beets from Canada, fresh turbot from the North Atlantic and papayas from Guatemala at ever-cheaper prices.

And Amazon’s purchase of Whole Foods may allow the e-commerce giant to court a much different customer. Walmart’s vast rural footprint often allows it to be the cheapest option in town, while Whole Foods’ stores are in more affluent areas.

Amazon recently began to creep into an important part of Walmart’s turf — low-income customers — when it slashed the price of its Amazon Prime membership for people with electronic benefits transfer cards, which people on food stamps and other government assistance programs use. Those customers pay $5.99 a month rather than the $10.99 a month or $99 a year other customers pay for Prime, which provides free two-day shipping, streaming video and other benefits.

The deal could also help solidify Amazon’s existing grocery business.

The company’s strategy could be “as much defensive as it is offensive,” said Burt P. Flickinger III, managing director of Strategic Resource Group, a global consulting firm. Mr. Flickinger recently returned from a research trip to Britain, where he said Lidl had significantly “slowed down” Amazon’s growth.

“Shoppers, vendors, people with whom we talked across the country said that Lidl literally transformed everybody’s standard of living, whether they shopped at Lidl or not,” he said. “They either stopped shopping at Amazon, or they shopped a lot less.”

As the supermarket war heats up, some grocery store chains, analysts said, may recognize they cannot compete in a grocery store price war.

“The bottom-tier operators are either going to have to close stores or they’re going to get sold to the next bigger guy in order to stay alive,” said Mickey Chadha, an analyst at Moody’s Corporation.

Morton Williams, a chain of upscale grocery stores in New York, has already adjusted to newer digital delivery services like Fresh Direct and Instacart. But now, executives fear how Amazon could use its digital expertise to expand Whole Foods in Manhattan.

“Fresh Direct and Instacart are already factored into our numbers,” said Avi Kaner, the co-owner of Morton Williams. “The thing that could result in greater risk to us is if Amazon invested in the Whole Foods locations in Manhattan to make them more delivery-centric.”

Tim Hayduk, 46, likes to shop at the Morton Williams near his office and also enjoys the sense of community that independent grocery stores engender. Now, he worries that more will disappear, as grocery stores big and small compete in an increasingly cluttered market.

“It’s sad to see the mom and pops disappear,” Mr. Hayduk said “The neighborhood grocery store is really important. You need a quick and easy place.”

A version of this article appears in print on June 17, 2017, on Page B1 of theNew York editionwith the headline: The Ultimate Food Fight.